As you are undoubtedly well aware, Steve Jobs unveiled the newest Apple money-suck toy product on Wednesday: the iPad. The most immediate response was to its tone-deaf name. I don't actually find feminine hygiene products to be disgusting, but it's hard not to laugh at jokes about iTampons or iKotex. That last joke really works best with medievalists; for everyone else, you need to spend so long explaining what a codex is, that the frog has been dissected and dead long before they know what to laugh at. But even aside from menstrual jokes, the best joke I've seen comes from a medievalist. Tom Elrod's blog post, "Introducing the iCodex," captures the breathless adoration of Steve Jobs's fans and the rediscovery of reading technology.

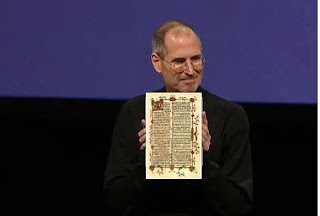

This image from the blog captures what's smart and funny about it, as does this excerpt:

With the iCodex, people can now store multiple items in one, easy-to-use package. A user could, for example, enjoy both cooking recipes and psalms, or mappa mundi and instructions on marital relations. Since the iCodex's pages are bound together in an easy-to-turn format, things stored at the end of an iCodex are as easy to access as the beginning.

You need to go read the whole thing in full to appreciate it. Go, I'll wait here.

After that, when you're ready for some serious responses to the iPad, check out Alex Payne's response, which focuses on the iPad not as an e-book, but as a very small and slick personal computer. As an e-book it might work well, but in a way that disturbs Payne deeply: "The iPad is an attractive, thoughtfully designed, deeply cynical thing. It is a digital consumption machine." As he goes on to discuss, turning a notebook into a tool for consumption rather than creation has implications for the future of hacking and programming and, I would argue, for the ways in which familiarity with computer languages retreats even further into the hands of a small few. Payne's argument is worth considering, especially in light of what I discussed in my last post about the ability to create mash-ups, whether in book form or in music. Consumption is great, but it's creation that makes a technology stick and a culture grow. (On the flip side of Payne's argument, Daniel Tenner praises the iPad for exactly these features: Apple is "making a slick “uncomputer” that’s tailored to those people who don’t actually need a computer.")

A couple of last notes: I found most of these posts through Twitter, thanks to @MagBaroque, @academicdave, and @briancroxall. Finally, the jokes connecting computers and medieval books have been around for a while. I've posted this before, and many of you will have already seen it, but I still love it, so I leave you with the Medieval Help Desk: