As I've spent more time reading on my iPad, I've come to more realizations about how I read. The most surprising thing is how much I miss sharing books. This is more complicated than it sounds. I knew, of course, that you can't really share e-books, but I have never really been someone who likes to share books. I'm happy to borrow books, but I get nervous loaning mine out. They come back beat up, or they don't come back at all and then I resent the person who has my book, or I can't remember who I loaned it to and it's gone forever. So I'm not a big book sharer. And since my family shares a single Kindle account, my spouse and my son and I can all share books across our devices--even better, we can read that book simultaneously on our separate devices. But what I failed to account for is the fact that I do actually loan out my books. Not often, and not with very many people. But there are a couple of friends I would like to be able to loan a book to, and sharing books with my sister was one of the important ways that we stayed connected with each other. I hadn't even realized how much it mattered to me to be able to exchange books with her until my Kindle reading got in the way. We're currently exploring sharing an account, since she and I have more similar tastes in reading than my husband and I do. (The fact that the Alpha Gadgeteer and I rarely enjoy the same books took me a long time to adjust to--it can be hard, when reading is so important to you, to not be able to share it with someone you love.) So sharing books with my sister makes a lot of sense, especially as it's a way of sharing our bond with each other in a pleasurable way, when so many of our other points of connection require more difficult emotions.

So one of the thing that I've rediscovered through reading on my iPad is that reading can be strongly tied to social connections. We exchange books as a way of saying, "I love you" or "I'm thinking of you" or any of a host of other emotions that connect us to each other.

Another thing that I've rediscovered is that we each individually read different texts in different ways. I had some sense of this in my post about false endings, in which I commented that most of my e-book reading was of thrillers, stories that pull me forward into their plot. But as I've spent more time with this contraption, and as I've let my book-buying habits expand, I've come to realize that there are some books I really would prefer to read in paper codex form. Some of this has to do with how I navigate the text: some works ask me to read them slowly, to revisit earlier passages, to refer back to past points in the narrative. Some works deserve to have a graphic presentation that reflects their content, a font that was chosen deliberately for them, a paper stock that makes up their heft, or their lack of it.

The iPad has worked fabulously well for me when I was reading Stieg Larsson's trilogy or Justin Cronin's The Passage. In fact, it worked ideally. I didn't have to wait to make it to a bookstore to start reading the 2nd book after I finished the 1st (something, of course, that was true only because I didn't start reading them until the entire series was out). And I didn't have to awkwardly hold the 700-plus pages of The Passage as I sped through it. (And I was less likely to throw my iPad against the wall in my annoyance at the ending than I would have been with the book itself. I know it's the first part of a trilogy, but sheesh!) And given that I do a lot of my reading at night, in bed, with my glasses off and the font greatly enlarged, I do speed through these books--there's not room for lots of words on the screen when you're reading in a big font. You just read, click, read, click, read, click. Any sense of physical movement through the book is greatly diminished. And that's fine. It worked with how I was experiencing those books anyway. I was reading them to find out what happened next. I cared about the characters and the language just enough to make me care about the plot.

But now I'm reading Howard Jacobson's The Finkler Question, and though I'm not very far into it, I'm finding that I really wish I was reading it in book form. I haven't been able to quite put my finger on it (there's an apt metaphor for you), but I need to be able to sink further into it, to take my time with it, and reading it on my iPad is somehow getting in the way of that.

It's possible this is less about the iPad and more about The Finkler Question. After my father died, a few years ago, I lost the ability to read any serious fiction. I was in the middle of reading English, August and it was a great book, but I put it down and couldn't pick it back up. Instead I picked up Tony Hillerman. And then I devoured a lot of P. D. James, and I discovered Laura Lippman, and a whole lot of not very good chick lit that I mostly don't recall. This got better, slowly, and I discovered that I could read What is the What, even though Philip Roth was off limits. I loved The Imperfectionists. And I never lost the ability to read some of my old favorites, like Jane Eyre. But I still sometimes hit an unexpected wall when I'm reading. I know other people who have had similar experiences, and I know that some people get back to their old ways of reading, and I continue to hope that will be true for me too.

My point in sharing this is that we have different ways of reading different books. I was fine reading novels about death. But there was a category of books that felt like they asked too much of me: I needed to commit to them, to enter into their world, to let them take charge of me. And perhaps it was that I felt too unsettled in my own world to do that, but I simply couldn't read those books. I needed to be able to stay on the surface of what I was reading.

So perhaps that's what my problem is with The Finkler Question. It's asking too much of me, and I'm still not ready to read that way. But I think, too, that the iPad has something to do with this. It's very easy to race through reading on the iPad. All texts look the same in the Kindle app, and sometimes they start to blur together. Maybe I can retrain myself to read more slowly even on my iPad, to take my time with the feel of the language. I might still be able to rewire some of my perceptual habits.

But I don't know that I will. I had an exchange with one of my children that made me think that as much as I do love reading on my iPad, I don't love all types of reading on my iPad. I had bought Philip Pullman's The Golden Compass for my son, and have been really pleased that he's been enjoying it. (He and I often do share similar tastes in reading, and to be able to share favorite books with your child is even more lovely than to share them with your spouse.) But I inadvertently ordered the mass market paperback for him, and the font is fairly small, especially compared to the books normally printed for kids to read. So although he's enjoying the book, he was feeling a bit frustrated with the print, and it seemed to me it was making the book a bit harder than it needed to be. He's enjoyed reading books on our Kindle before, so I bought the Kindle edition of The Golden Compass--less than $8 and then I can read it on my iPad along with him! But he soon decided that he preferred reading it as a book. Yes, the type was bigger on the Kindle, and yes, he'd enjoyed reading some Rick Riordan books on it. But this time it wasn't working for him. It felt better as a book. I think he felt similar to how I feel about The Finkler Question. Some books you need to focus on, and you need to do that in book form.

Showing posts with label technologies. Show all posts

Showing posts with label technologies. Show all posts

Friday, October 8, 2010

Friday, September 3, 2010

DIY newsbook

No, I don't mean it's time to write your own news sheet newsbook. It's time to fold your own

Above is a numbered example of the same

You can follow this link and print off the two images as a single sheet of paper (or print separately, of course, and then run them through a copier to make it two-sided) and practice folding it as a quarto yourself. When you're done, you can try folding it into a tiny little pressman's cap, following the instructions that appear in this lovely piece, "The Newspaper Man is Defunct," from The Cape Cod today.

By the way, my syllabus is now done(ish) and can be found online in pdf form.

Correction: The spelling of recto has been changed to reflect its actual spelling. Oops.

Correction 2: I have corrected my usage of "news sheet" to reflect the more accurate term "newsbook" throughout the post. See the comments below for an explanation of the difference between the two!

Above is a numbered example of the same

You can follow this link and print off the two images as a single sheet of paper (or print separately, of course, and then run them through a copier to make it two-sided) and practice folding it as a quarto yourself. When you're done, you can try folding it into a tiny little pressman's cap, following the instructions that appear in this lovely piece, "The Newspaper Man is Defunct," from The Cape Cod today.

By the way, my syllabus is now done(ish) and can be found online in pdf form.

Correction: The spelling of recto has been changed to reflect its actual spelling. Oops.

Correction 2: I have corrected my usage of "news sheet" to reflect the more accurate term "newsbook" throughout the post. See the comments below for an explanation of the difference between the two!

Labels:

material text,

printing,

technologies

Thursday, July 29, 2010

false endings

I've been thinking a lot recently about the experience of reading. Part of this is about the technologies of reading, but part of this is about the nature of reading and processing words.

Some context is helpful here: this spring we sold our house and moved into a new house. As part of this process, we overhauled the old house, cleaning it out and making it look fabulously inviting (those of you who watch a lot of HGTV or live in housing-market-obsessed areas will recognize this as "staging", a term that deserves its own post on an entirely different blog). We bowed to the wisdom of our realtor, who went through our house and identified the furniture and clutter that ought to be cleared out. Right up at the top of the list were all of our bookshelves and, obviously, books. This is the point when my bookish friends yelp in horror--"Why are books unattractive?!"--but as someone who has been shopping for houses, I have to agree with the realtor on this point. Books mark a space as belonging to a specific person, someone, in this case, who is not you. If you are a Jane Austen fan, are you going to see yourself living in a space marked by Dan Brown books? I can't tell you the number of times I looked at a house and instead of being perplexed by the kitchen layout found myself thinking, "do these people really need to own so many books about football?" Equally crucial is the point that bookcases take up room--if you've got two walls lined with books, the livable space of the room feels tinier, and who wants to buy a house that is already clearly tiny and cramped? In any case, we packed up all our books. We own a lot of books. Seventy boxes of books, in fact. We packed them up in mid-April, and, for a variety of reasons having to do with renovations and the chaos of moving, those books remain boxed up and will probably stay boxed up for another six to nine months.

When I see it written down like that, I want to cry--that's a long time to go without my books! But while I miss my physical books, I have not stopped reading. But instead of buying books, or checking books out of my library (that's a different problem I won't go into here), I now read e-books on a variety of devices: Kindle, iPad, iPod Touch. And, it turns out, I love reading on these devices. I love that with the Kindle app I can start off reading a book on a Kindle, transfer it to my iPod, and sync it so that my son can devour his own novel on the Kindle while I'm at work. At night I can read on my iPad, with grey words glowing on black background without ever waking my husband, The Alpha Gadgeteer (it's thanks to him that we have this plethora of devices). And, oh, the seduction of being able to think of a book you'd like to read, buy it, and start reading it seconds later!

This isn't a post about the pros and cons of e-books and the readers that are out there, however. Rather, I've been struck by some of the differences between the experience of reading on the iPad and reading a book. For starters, and this continues to catch me out, when I'm reading on the iPad I have no sense of the passage of travel through the narrative. What I mean is, if I need to go back to double-check something that happened earlier, I have no sense of how many screens back it is--I'll think it's just a couple of finger swipes, but it's really a couple dozen swipes. The same thing happens at the end of the book--I have no idea how close to the end of the story I am. Is this seeming wrap-up of the action the false ending that lulls you into a calm before Jason bursts up from the lake and the last survivor has to take him on yet again? (I know I've mixed my book and movie references there, but that moment in Friday the 13th continues to haunt me, decades later. Perhaps it's the glossiness of the iPad that makes me think about movies; that and the fact that I've been reading lots of thrillers on it.) With a book in your hand, you have a sense of how many pages are left before the narrative wraps up, assuming that it's not a cliff-hanger or that the end of the book isn't padded with the opening chapters of the next book in a series. With the iPad Kindle app, there is no continuously visible marker of passage though the text. You read until you done, and you know you're done because you swipe your finger and the cover appears. (Yes, the cover. The app begins the book on what it thinks is the first page of main text, which means that in some books, you have to go backwards until you get to the start of the prologue.)

This realization that I don't know where I am in the forward movement of the story points to something oddly old-fashioned about reading this way, something that James O'Donnell has noted, too:

I expect I'll adjust to the newness of the iPad and will someday no longer be caught out by the surprise of a story ending before I realize it. And I certainly don't always want to read in this linear fashion (there's a reason why I've been reading the type of fiction I have on it, but not any of the scholarship that I otherwise read). But for right now, it's fun to experience reading in a different way.

This is a pretty short and easy post as I try to get back in the habit of blogging again. I hadn't meant to be gone for so long, but sometimes life gets in the way (see that whole packing/selling/buying/moving drama above). As the fall approaches I am again thinking about early modern books, how to teach book history, and how to marry new technologies with old books. For the couple of you who might have hung in there during my long absence, it's nice to see you again, and I'll do better by you in the future!

Some context is helpful here: this spring we sold our house and moved into a new house. As part of this process, we overhauled the old house, cleaning it out and making it look fabulously inviting (those of you who watch a lot of HGTV or live in housing-market-obsessed areas will recognize this as "staging", a term that deserves its own post on an entirely different blog). We bowed to the wisdom of our realtor, who went through our house and identified the furniture and clutter that ought to be cleared out. Right up at the top of the list were all of our bookshelves and, obviously, books. This is the point when my bookish friends yelp in horror--"Why are books unattractive?!"--but as someone who has been shopping for houses, I have to agree with the realtor on this point. Books mark a space as belonging to a specific person, someone, in this case, who is not you. If you are a Jane Austen fan, are you going to see yourself living in a space marked by Dan Brown books? I can't tell you the number of times I looked at a house and instead of being perplexed by the kitchen layout found myself thinking, "do these people really need to own so many books about football?" Equally crucial is the point that bookcases take up room--if you've got two walls lined with books, the livable space of the room feels tinier, and who wants to buy a house that is already clearly tiny and cramped? In any case, we packed up all our books. We own a lot of books. Seventy boxes of books, in fact. We packed them up in mid-April, and, for a variety of reasons having to do with renovations and the chaos of moving, those books remain boxed up and will probably stay boxed up for another six to nine months.

When I see it written down like that, I want to cry--that's a long time to go without my books! But while I miss my physical books, I have not stopped reading. But instead of buying books, or checking books out of my library (that's a different problem I won't go into here), I now read e-books on a variety of devices: Kindle, iPad, iPod Touch. And, it turns out, I love reading on these devices. I love that with the Kindle app I can start off reading a book on a Kindle, transfer it to my iPod, and sync it so that my son can devour his own novel on the Kindle while I'm at work. At night I can read on my iPad, with grey words glowing on black background without ever waking my husband, The Alpha Gadgeteer (it's thanks to him that we have this plethora of devices). And, oh, the seduction of being able to think of a book you'd like to read, buy it, and start reading it seconds later!

This isn't a post about the pros and cons of e-books and the readers that are out there, however. Rather, I've been struck by some of the differences between the experience of reading on the iPad and reading a book. For starters, and this continues to catch me out, when I'm reading on the iPad I have no sense of the passage of travel through the narrative. What I mean is, if I need to go back to double-check something that happened earlier, I have no sense of how many screens back it is--I'll think it's just a couple of finger swipes, but it's really a couple dozen swipes. The same thing happens at the end of the book--I have no idea how close to the end of the story I am. Is this seeming wrap-up of the action the false ending that lulls you into a calm before Jason bursts up from the lake and the last survivor has to take him on yet again? (I know I've mixed my book and movie references there, but that moment in Friday the 13th continues to haunt me, decades later. Perhaps it's the glossiness of the iPad that makes me think about movies; that and the fact that I've been reading lots of thrillers on it.) With a book in your hand, you have a sense of how many pages are left before the narrative wraps up, assuming that it's not a cliff-hanger or that the end of the book isn't padded with the opening chapters of the next book in a series. With the iPad Kindle app, there is no continuously visible marker of passage though the text. You read until you done, and you know you're done because you swipe your finger and the cover appears. (Yes, the cover. The app begins the book on what it thinks is the first page of main text, which means that in some books, you have to go backwards until you get to the start of the prologue.)

This realization that I don't know where I am in the forward movement of the story points to something oddly old-fashioned about reading this way, something that James O'Donnell has noted, too:

The Kindle is great for reading the way ancient Greeks read, on papyrus scrolls, beginning at the beginning, proceeding linearly, getting to the end, absorbed in one book, following the author's lead.While the technology delivering the text is new-fangled, the reading itself is decidedly not. (O'Donnell, who is a classicist and Provost of Georgetown University, knows something about how ancient Greeks read; he has a short piece about his Kindle in the Chronicle of Higher Education, from which the above is quoted. He also delivered a talk at Yale's Sterling Memorial Library on "A Scholar Gets a Kindle and Starts to Read" this past April which you can watch on YouTube.)

I expect I'll adjust to the newness of the iPad and will someday no longer be caught out by the surprise of a story ending before I realize it. And I certainly don't always want to read in this linear fashion (there's a reason why I've been reading the type of fiction I have on it, but not any of the scholarship that I otherwise read). But for right now, it's fun to experience reading in a different way.

This is a pretty short and easy post as I try to get back in the habit of blogging again. I hadn't meant to be gone for so long, but sometimes life gets in the way (see that whole packing/selling/buying/moving drama above). As the fall approaches I am again thinking about early modern books, how to teach book history, and how to marry new technologies with old books. For the couple of you who might have hung in there during my long absence, it's nice to see you again, and I'll do better by you in the future!

Labels:

navigational aids,

reading,

technologies

Sunday, January 31, 2010

quick iPad roundup

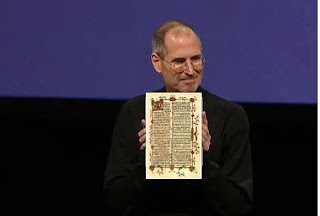

As you are undoubtedly well aware, Steve Jobs unveiled the newest Apple money-suck toy product on Wednesday: the iPad. The most immediate response was to its tone-deaf name. I don't actually find feminine hygiene products to be disgusting, but it's hard not to laugh at jokes about iTampons or iKotex. That last joke really works best with medievalists; for everyone else, you need to spend so long explaining what a codex is, that the frog has been dissected and dead long before they know what to laugh at. But even aside from menstrual jokes, the best joke I've seen comes from a medievalist. Tom Elrod's blog post, "Introducing the iCodex," captures the breathless adoration of Steve Jobs's fans and the rediscovery of reading technology.

This image from the blog captures what's smart and funny about it, as does this excerpt:

With the iCodex, people can now store multiple items in one, easy-to-use package. A user could, for example, enjoy both cooking recipes and psalms, or mappa mundi and instructions on marital relations. Since the iCodex's pages are bound together in an easy-to-turn format, things stored at the end of an iCodex are as easy to access as the beginning.

You need to go read the whole thing in full to appreciate it. Go, I'll wait here.

After that, when you're ready for some serious responses to the iPad, check out Alex Payne's response, which focuses on the iPad not as an e-book, but as a very small and slick personal computer. As an e-book it might work well, but in a way that disturbs Payne deeply: "The iPad is an attractive, thoughtfully designed, deeply cynical thing. It is a digital consumption machine." As he goes on to discuss, turning a notebook into a tool for consumption rather than creation has implications for the future of hacking and programming and, I would argue, for the ways in which familiarity with computer languages retreats even further into the hands of a small few. Payne's argument is worth considering, especially in light of what I discussed in my last post about the ability to create mash-ups, whether in book form or in music. Consumption is great, but it's creation that makes a technology stick and a culture grow. (On the flip side of Payne's argument, Daniel Tenner praises the iPad for exactly these features: Apple is "making a slick “uncomputer” that’s tailored to those people who don’t actually need a computer.")

A couple of last notes: I found most of these posts through Twitter, thanks to @MagBaroque, @academicdave, and @briancroxall. Finally, the jokes connecting computers and medieval books have been around for a while. I've posted this before, and many of you will have already seen it, but I still love it, so I leave you with the Medieval Help Desk:

Labels:

medieval books,

technologies

Sunday, January 17, 2010

early modern mash-ups

In my last post wondering about important book history

But the growing interest in and the plethora of music and video mash-ups speaks to me more as being about how the availability of technology deeply affects (and effects) our responses to art. We can talk all we want about how something like dj erb's Hollaback Girl of Constant Sorrow reflects a post-modern (or is that post-post-modern?) notion of authorship and female sexuality and the American past, but what strikes me is how technology makes possible new expressions of creativity and their distribution. Without recording technology that separates instrumental and vocal tracks and without the availability of computers to remix those tracks with other tracks unintended by the first creators, none of this would be possible. The tools that enabled artists to create their music also enables listeners to turn into artists, modifying that music in ways that honor it, subvert it, and most of all make it our own.

Now what, exactly, does this have to do with early modern books? We have all, I think, started to at least pay lip service to the notion that all early modern plays were collaborative efforts, drawing on the talents and influences of (often) multiple playwrights, players, and company sharers. (Even Shakespeare collaborated! Shh, don't tell Harold Bloom!) We are also, I hope, increasingly aware that all printed works were also collaborations, shaped by writers, publishers, and printers. But I also believe that all printed works were also collaborations with their readers. This isn't just a belief in response response theory. It's a belief that the users of books reshaped them as they needed to, sometimes literally. As Jeffrey Todd Knight makes clear in his recent--and excellent--article in the Fall 2009 issue of Shakespeare Quarterly, early readers of Shakespeare's plays and poems combined them with other printed works to create self-shaped anthologies. Part of Knight's point is that early modern readers bound works together in ways that suggest contexts and connections that have now been lost to us, as later collectors ruthlessly prioritized Shakespeare over other writers and disbound such groupings in order to rebind Shakespeare as a solitary work. It's an important recognition for those of us interested in early printed books and in the histories they accrue in the hands of collectors and libraries. Shakespeare was not separate from his contemporaries, but part and parcel.

One thing that I take away from Knight is that such context been lost. So, too, has the sense that books are made by their users. We might want to think of these gatherings as early mash-ups: books that readers remade into their own books. The technology of printed books allows for such mash-ups. Books can be joined together because they are (particularly smaller formats) sold unbound, requiring their owners to choose whether or not to have them bound and how to have them bound. The comparatively cheap cost of printed books, as opposed to manuscripts, meant that there were enough being sold and bought that such collections proliferated.

The image at the top of this post is a manuscript listing of the contents of such a collection (catalog record; zoomable image). It identifies fifteen plays and entertainments, including works by Carew, Chapman, Heywood, Jonson, and Shakespeare. Knight discusses it in his article, along with a number of other examples. (You can read the abstract of his essay; if you have access to Project MUSE, you can read the article itself online.) If you'd like to read some other musings along these lines, Whitney Trettien has a series of posts on cut-ups at diapsalmata that think not only about early modern instances, but about modern cut-ups as well.

Since I started off with my look back at the last year, I leave you with this: DJ Earworm's mash-up of the United State of Pop 2009. Enjoy!

Labels:

authorship,

material text,

Shakespeare,

technologies

Tuesday, December 22, 2009

the most influential book history tools of the decade

It's that time of year again. Indeed, it's that time of decade. That's right, everywhere you look, top ten lists abound. I'm not sure why we need to list ten of things we find remarkable. But it's made me start thinking: what would be on my top ten list of notable early modern book history events or tools of the decade?

It's that time of year again. Indeed, it's that time of decade. That's right, everywhere you look, top ten lists abound. I'm not sure why we need to list ten of things we find remarkable. But it's made me start thinking: what would be on my top ten list of notable early modern book history events or tools of the decade?Right up there at the top would have to be digitization, from EEBO to Google Books to The Shakespeare Quartos Archive. The ability to access facsimiles of works without having to travel thousands of miles, potentially saving time and money and carbon emissions and wear and tear on the books, has fundamentally changed how we conduct and teach early modern books and book history. EEBO and Google Books have been mostly about access, but Shakespeare Quarto Archive is not only about access but about developing digital tools for studying texts. (Read my posts on digitization to see some of the pros and cons I see with this development, since it's too complicated of a subject to rehearse here. Again.)

I'd say, too, that book history and early modern blogs have seen remarkable growth over the past ten years. Blogs have enabled a conversation between far-flung scholars and devotees of early books that wouldn't be otherwise possible. I've learned a lot from Mercurius Politicus and diapsalmata, as well as Early Modern Online Bibliography and Bavardess (I've learned from many others, too, and have links to them on my blog--this is just a ruthless short list of a handful that I go to the most often). They've done good things for libraries, too, opening up interest in collections and, I like to imagine, the use of our materials, across levels of scale and resources. The Beinecke has a great bunch of blogs (early modern, paleography), and I enjoy reading "Notes for Bibliophiles" from the Special Collections at the Providence Public Library. I've pleaded before for more early modern literature blogs, but I've really enjoyed what is out there, literature or not, early modern or post modern. Especially as someone who only came to this field a few years ago, I've learned a lot from reading your blogs and have been grateful for being part of this community.

This one is a bit more idiosyncratic, but watching my kids learning to read has given me a new appreciation for reading in general and for the emotional ties we have to books. Over the past ten years I've seen both my kids start reading and start loving books; I've actually also gotten to see both of them start learning Hebrew as well, which brings home the whole weirdness of written languages and learning to recognize letters as making up words and those words as having recognizable (and deployable) meanings. I continue to find the transition from gobbledygook to spoken language amazing, and the movement from spoken to written language is equally fascinating. I have one child who refused to read on his own until he had it mastered; the first book he read was The Borrowers, which is crazy ridiculous for a first-time book. My other child insisted on figuring out the reading thing before he'd even started school and made tons of mistakes along the way; those rhyming books like "Pat sat on the cat" were a key exercise for him, if a bit tedious for me. Watching them learning to read in their own ways provided insight into literacy in a way that I otherwise wouldn't have appreciated. What does it mean to be literate? Does it mean to haltingly read rhyming books? To understand the metaphorical implications of Bilbo's fight against Smaug? To pronounce written characters in words whose meaning you cannot understand? (For something of the emotional resonance of reading with children, see this post.)

This might also be myopic, but I think a growing interest in the pedagogy of book history and bibliography has been another development. In my discipline of English literature, at least, bibliography and textual studies had a marked decline in graduate programs--when I was in grad school in the early 1990s, in a program that is now characterized by a strong interest in the history of the book, there were not only no requirements for mastering descriptive bibliography or editing, there were few opportunities to learn those subjects. My sense, without having conducted formal studies of the subject, is that this was characteristic of the field in those years. Once upon a time, PhD students were required to have a knowledge of bibliography and editing; those requirements fell by the wayside, and an interest in those subjects has only recently reemerged and trickled down into graduate and undergraduate programs. As someone who runs a program teaching these subjects to undergraduates, I might easily be accused of myopia here, but I do think that an increased interest in teaching these subjects is not characteristic only of the Folger but of many programs. (I've blogged some examples of the work my students have done in my courses.)

Back to technology, here's another one that people didn't necessarily see coming: audiobooks. That's right, the rise of the iPod has led not only to the rise of iExcess, but to an increase in audiobooks. Remember when we used to listen to books on tape? Remember how awkward they were, how limited the selection was? I used to go to my public library (the fab Philadelphia Free Library) to try to find books on tape to get me through the ten-hour drive home to Michigan. It wasn't so easy to do. But now, thanks in part to Audible's large library, there are a slew of options out there. And listening on your iPod is so much easier than flipping tapes over. Neil Gaiman had a nice piece on NPR last month pointing out the unexpected rise in audiobooks. I love me a good audiobook. But I love, too, the way this reminds us that technology doesn't always have the effect we expect it to. Audiobooks were on their way out, and the decline of the cassette tape seemed only to confirm that fade. But then came along MP3s, and the rebirth of audiobooks.

I am, alas, only up to five, which is well short of the ten that make up most lists. So I turn to you, dear readers, to help flesh this out. What would you point to as developments over the past decade that have shaped our understanding of early modern books and book history? Twitter? Amazon? The recovery of Durham's stolen First Folio? Kindle? The pdf of the Stationers' Register? Don't let my perspective dictate yours--I'd be thrilled to expand my horizons with your help!

And with my advance thanks for your thoughts on this subject, please add my best wishes for a happy new year!

Labels:

blogging,

students,

technologies

Sunday, October 11, 2009

to e-book or not to e-book

There's been a slew of stories over the last few months about electronic books, primarily of the Kindle variety, but some of them touch on general issues pertaining to the availability, use, and desirability of e-books. I've been trying to compose a post in response to them, but I keep getting overwhelmed. What to say in response to a prep school that replaces its library with a cappuccino machine and 18 e-readers? *head-desk* (The School Library Journal has a more articulate response.) What about the summer's too-perfect-to-be-true news that Amazon deleted copies of Orwell's works from the Kindles without informing owners? Make that another big #amazonfail moment after their first, horrendous mistake last spring when changes in their ranking system made thousands of gay and lesbian titles disappear from searches. Ooops. In further e-stories, there's the non-release as e-books of two of the Fall's big titles: Teddy Kennedy's posthumous True Compass and Sarah Palin's Going Rogue. What will those Cushing Academy students do when researching papers about the Obama election? I guess rely on Wikipedia. (For insight into why the memoirs aren't Kindled, see Daniel Gross's Moneybox column for Slate, in which he explains why the economics of publishing doesn't make sense for them as e-reads.) Oh, and speaking of students and e-readers, what do Princeton students have to say about using Kindles as part of a pilot program to replace textbooks with Kindles? According to one student quoted in the Daily Princetonian, "this technology is a poor excuse of an academic tool." Finally, last week there was the New York Times piece worrying that books might be the next to be "Napsterized." (Remember Napster? Some of you young 'uns might not recall the world before digital music files, but let me tell you, it put the fear of Someone into the music industry when people started sharing their music online.) Joshua Kim's response on Inside Higher Ed brings those Napster concerns into a conversation with universities and libraries.

About a year ago, I posted about my perplexed response to a newspaper column that touted the joy of Kindle as being "almost like a book"--why read something that's almost as good as a book when you could read a book? I still stand by that point, but not because I'm a luddite. In that particular piece, I was reacting against a perception that e-reading had to be good because it was new. But I also don't think it has to be bad because it's new. My husband got a Kindle last spring and it's been great. For him, the joy of the machine is that it holds so much. Given his preference for texts that come in big, heavy books--military history, science fiction, jurisprudence--the fact that he can take his Kindle on trips means that he needn't break his back or run out of reading material. I still don't use it, and not only because he's the alpha gadgeteer in our household. My way of reading for work and research is to cover the page in notes, so paper copies work best for me. And most of my pleasure reading I do in a way that isolates me as much as possible from the world: glasses off, dark room, book light. We all have our own ways of reading and different technologies that meet those needs.

But much of what I'm seeing written in the popular press about e-book readers isn't, I don't think, taking into account the full picture. Some of the stories I mentioned above hint at the problem of Amazon's essential monopoly over the current e-field. I know Sony has an e-reader, but given Amazon's vertical integration, they hold an incredible portion of the e-market in their tight e-fist. (E-sorry. It's hard to stop the e-jokes.) If there was some competition in that market, the problems of pricing and availability and Big Brother would be different.

More to this blog's point, what does the current state of e-readers and discussion have to do with book history and book historians? So much of what we're considering today with Kindles focuses on books that were written to be distributed in print and then are transferred into an e-format. (Daniel Gross's book Dumb Money actually did this transference the other direction: he wrote it as an e-book for Free Press and it sold well enough that it's now available in print--see the Washington Post profile of him for more on that.) But what happens when we get to the day that works are created for and intended to be experienced as e-books? How will that change the experience of using books? And how will we ensure the survival of those books? As anyone who has been working with computers over the last few decades knows, technology becomes obsolete and earlier formats don't always carry over into new ones.

Similarly, how might the availability of new digital formats affect the process of creating works? According to Scott Karambis, for some creative artists, the availability of the digital world has changed how and what they write: author Justin Cronin relied on the ease of researching online to push his knowledge into new arenas when composing his newest novel, insisting that it made him become a different sort of writer. Karambis's blog post focuses more on the effect of technology on the process of creation and less on the impact of digital creations themselves (the blog is geared towards other folks in marketing, rather than, say, writers or book historians). Rachel Toor, writing in the Chronicle of Higher Education, is more focused on the economic impact of e-books. Even though she loves reading e-books on her Kindle, she has decidedly more mixed feelings about being an e-writer. Might e-publishing save university publishers by bringing down costs and therefore recovering the economic viability of those scholarly monographs with small audiences? And the speed of electronic publishing is wonderful for timely subjects and for the responsiveness it generates for readers. But will people stumble across e-books the way they do physical books on bookshelves? Will writers be able to live off the advances from their e-books the way that some are able to today?

Toor and Cronin don't ask this in their reflections on writing and new technology, but I will: will we still have e-books to read if they aren't backed up on paper? Will we still be able to lend books to each other if they're tied to our e-readers? Will we still be able to talk back to our books, modify them, resist them?

I often, when teaching early modern book history, say to my students, "It's all about money!" And it often is. But it's also about creativity and interactivity and longevity. And we're still taking baby steps towards what it all might mean.

About a year ago, I posted about my perplexed response to a newspaper column that touted the joy of Kindle as being "almost like a book"--why read something that's almost as good as a book when you could read a book? I still stand by that point, but not because I'm a luddite. In that particular piece, I was reacting against a perception that e-reading had to be good because it was new. But I also don't think it has to be bad because it's new. My husband got a Kindle last spring and it's been great. For him, the joy of the machine is that it holds so much. Given his preference for texts that come in big, heavy books--military history, science fiction, jurisprudence--the fact that he can take his Kindle on trips means that he needn't break his back or run out of reading material. I still don't use it, and not only because he's the alpha gadgeteer in our household. My way of reading for work and research is to cover the page in notes, so paper copies work best for me. And most of my pleasure reading I do in a way that isolates me as much as possible from the world: glasses off, dark room, book light. We all have our own ways of reading and different technologies that meet those needs.

But much of what I'm seeing written in the popular press about e-book readers isn't, I don't think, taking into account the full picture. Some of the stories I mentioned above hint at the problem of Amazon's essential monopoly over the current e-field. I know Sony has an e-reader, but given Amazon's vertical integration, they hold an incredible portion of the e-market in their tight e-fist. (E-sorry. It's hard to stop the e-jokes.) If there was some competition in that market, the problems of pricing and availability and Big Brother would be different.

More to this blog's point, what does the current state of e-readers and discussion have to do with book history and book historians? So much of what we're considering today with Kindles focuses on books that were written to be distributed in print and then are transferred into an e-format. (Daniel Gross's book Dumb Money actually did this transference the other direction: he wrote it as an e-book for Free Press and it sold well enough that it's now available in print--see the Washington Post profile of him for more on that.) But what happens when we get to the day that works are created for and intended to be experienced as e-books? How will that change the experience of using books? And how will we ensure the survival of those books? As anyone who has been working with computers over the last few decades knows, technology becomes obsolete and earlier formats don't always carry over into new ones.

Similarly, how might the availability of new digital formats affect the process of creating works? According to Scott Karambis, for some creative artists, the availability of the digital world has changed how and what they write: author Justin Cronin relied on the ease of researching online to push his knowledge into new arenas when composing his newest novel, insisting that it made him become a different sort of writer. Karambis's blog post focuses more on the effect of technology on the process of creation and less on the impact of digital creations themselves (the blog is geared towards other folks in marketing, rather than, say, writers or book historians). Rachel Toor, writing in the Chronicle of Higher Education, is more focused on the economic impact of e-books. Even though she loves reading e-books on her Kindle, she has decidedly more mixed feelings about being an e-writer. Might e-publishing save university publishers by bringing down costs and therefore recovering the economic viability of those scholarly monographs with small audiences? And the speed of electronic publishing is wonderful for timely subjects and for the responsiveness it generates for readers. But will people stumble across e-books the way they do physical books on bookshelves? Will writers be able to live off the advances from their e-books the way that some are able to today?

Toor and Cronin don't ask this in their reflections on writing and new technology, but I will: will we still have e-books to read if they aren't backed up on paper? Will we still be able to lend books to each other if they're tied to our e-readers? Will we still be able to talk back to our books, modify them, resist them?

I often, when teaching early modern book history, say to my students, "It's all about money!" And it often is. But it's also about creativity and interactivity and longevity. And we're still taking baby steps towards what it all might mean.

Labels:

digitization,

technologies

Sunday, August 16, 2009

the primer in englishe and latine

Last year, at the start of each semester, I gave you something from a school book to celebrate the return of classes: in the fall it was Lily's Latin grammar; in the spring, Comenius's picture book. This semester, I think I'll give you something slightly different to celebrate the return of students: a look at some of the books my students worked with last spring.

First up, this 1557 English book of hours:

The student who was working on this book was a theology major and chose it, I think, to have a chance to think about Catholic liturgy and print. There's a lot to be learned about liturgy in studying it. The title of the book signals some of the basic issues at play: The primer in Englishe and Latine, set out along, after the use of Sa[rum]: with many godlie and devoute praiers: as it apeareth in the table. A brief history of primers in encapsulated in that title. There's the reference to "Sarum use", specifying this book of hours as following the Salisbury rite, the form that dominated England Catholic liturgy. Most notable is the identification that this includes a translation of the Latin prayers into English, an increasingly popular approach to the prayers after the Reformation, and one that was strictly regulated. That this is in both Latin and English links it to a specific historical moment. It wasn't until after Henry VIII's split with the Catholic Church that books of hours in English (usually referred to as "primers") began to be published in England--and Henry, after 1545, promulgated his Royal Primer. With Mary's reign, the Sarum rite again became the sanctioned form of the primer, though the popularity of English translations continued. The imprint of this book hints at the Sarum primer's popularity: "Imprinted at London, by Jhon Kyngston, and Henry Sutton. 1557. Cum privilegio ad imprimendum solum." You could assume correctly from the "cum privilegio" that printing primers was a lucrative business that was awarded to a specific printer. You could correctly assume, too, that we would see a rise of English Sarum primers printed during Mary's reign.

That's a brief outline of some of what we can learn from the title page--a sort of cultural/political/religious history that can be gathered from studying this book. But we can do something fun, too, with the mise-en-page of this book:

This opening is mostly fairly typical: there's the English translation in the large columns closest to the gutter in a nice blackletter font, and the Latin text in the outer columns in a smaller font. The decorated initials are printed woodcuts (that is, not hand-rubricated or illuminated). And the running titles and other directive texts are printed in red ink to guide the reader. All of these details can lead you into a study of how this book was designed to be used.

But there's something else we can learn from this book, too. Here's a close-up showing the text in more detail, including my favorite moment:

Did you notice it? Take a look again.

What is the title given to this prayer, which begins "Rejoyce O virgine Christes mother deare"? Is it "Of the five corporall joyes of our Ladie."? But why is "Ladie" printed in black? Look underneath--it was first printed "of our lorde." Ooops. Well, anyone can make a mistake, right? At least they corrected it. And that's what I love about this page. Here's the thing--printers did not typically print red and black ink at the same time. Think about it--it would be pretty hard to dab black ink only on the black bits and red ink on the red bits. You wouldn't be able to do it with your standard ink balls.

Instead, you'd follow a much more complicated series of steps. First, you'd set the type for the whole form (that is, not just one single page, but all the pages on that side of the sheet). Then you'd determine which words were to be printed in red, take those letters out and replace them with blanks. You'd ink the whole thing with black, using those ink balls that have been keeping nice and moist by soaking in urine, and run it through the press once with black ink. After you'd run through the entire run's worth of copies of that form, it would be time to do the red ink. You'd cut a new frisket (the protective sheet that covers over what you don't want to get inked) that would have holes for the red text but keep the black text covered. You'd replace the blanks with the red text, which has been raised slightly above the black text so that when you pull the press, only the raised type will print. And then you would run the entire set of sheets through the press again. If you've done it all right, the red text will print in the holes that were left behind after the black ink run. As you can see from this book, sometimes the red and black ink printed a bit more askew. (You can find a tidier example of two-color printing at this earlier blog post.)

So here's where I really love this: the printers, after making this mistake, recognize it, and want, understandably, to fix it--which means running the entire thing through the press for a third time! Oh, the labor of it all!

That's what I'm going to think of at the start of the fall: sometimes learning and teaching doesn't happen on the first try, or even the second. But that's no reason to stop working! This is also a good reminder of how much of what we do is serendipitous--looking up this book in the catalogue, there was no sign of this cool printing tidbit. It was only because Caitlin looked through every single page in this book with her eyes wide open that she found it. What a nice reward for her curiosity! And that feels like another excellent piece of advice for all of us: don't forget to be curious along the way and to be open to discovering something new.

Happy learning!

(Want to read about printing with red ink in more detail? Joseph Moxon's Mechanick Exercises, as always, is your not-to-be-beat source about early printing; for the section on two-color printing, see pages 328-30. This lovely primer can be found in our catalogue here; a set of zoomable images from it are here.)

First up, this 1557 English book of hours:

The student who was working on this book was a theology major and chose it, I think, to have a chance to think about Catholic liturgy and print. There's a lot to be learned about liturgy in studying it. The title of the book signals some of the basic issues at play: The primer in Englishe and Latine, set out along, after the use of Sa[rum]: with many godlie and devoute praiers: as it apeareth in the table. A brief history of primers in encapsulated in that title. There's the reference to "Sarum use", specifying this book of hours as following the Salisbury rite, the form that dominated England Catholic liturgy. Most notable is the identification that this includes a translation of the Latin prayers into English, an increasingly popular approach to the prayers after the Reformation, and one that was strictly regulated. That this is in both Latin and English links it to a specific historical moment. It wasn't until after Henry VIII's split with the Catholic Church that books of hours in English (usually referred to as "primers") began to be published in England--and Henry, after 1545, promulgated his Royal Primer. With Mary's reign, the Sarum rite again became the sanctioned form of the primer, though the popularity of English translations continued. The imprint of this book hints at the Sarum primer's popularity: "Imprinted at London, by Jhon Kyngston, and Henry Sutton. 1557. Cum privilegio ad imprimendum solum." You could assume correctly from the "cum privilegio" that printing primers was a lucrative business that was awarded to a specific printer. You could correctly assume, too, that we would see a rise of English Sarum primers printed during Mary's reign.

That's a brief outline of some of what we can learn from the title page--a sort of cultural/political/religious history that can be gathered from studying this book. But we can do something fun, too, with the mise-en-page of this book:

This opening is mostly fairly typical: there's the English translation in the large columns closest to the gutter in a nice blackletter font, and the Latin text in the outer columns in a smaller font. The decorated initials are printed woodcuts (that is, not hand-rubricated or illuminated). And the running titles and other directive texts are printed in red ink to guide the reader. All of these details can lead you into a study of how this book was designed to be used.

But there's something else we can learn from this book, too. Here's a close-up showing the text in more detail, including my favorite moment:

Did you notice it? Take a look again.

What is the title given to this prayer, which begins "Rejoyce O virgine Christes mother deare"? Is it "Of the five corporall joyes of our Ladie."? But why is "Ladie" printed in black? Look underneath--it was first printed "of our lorde." Ooops. Well, anyone can make a mistake, right? At least they corrected it. And that's what I love about this page. Here's the thing--printers did not typically print red and black ink at the same time. Think about it--it would be pretty hard to dab black ink only on the black bits and red ink on the red bits. You wouldn't be able to do it with your standard ink balls.

Instead, you'd follow a much more complicated series of steps. First, you'd set the type for the whole form (that is, not just one single page, but all the pages on that side of the sheet). Then you'd determine which words were to be printed in red, take those letters out and replace them with blanks. You'd ink the whole thing with black, using those ink balls that have been keeping nice and moist by soaking in urine, and run it through the press once with black ink. After you'd run through the entire run's worth of copies of that form, it would be time to do the red ink. You'd cut a new frisket (the protective sheet that covers over what you don't want to get inked) that would have holes for the red text but keep the black text covered. You'd replace the blanks with the red text, which has been raised slightly above the black text so that when you pull the press, only the raised type will print. And then you would run the entire set of sheets through the press again. If you've done it all right, the red text will print in the holes that were left behind after the black ink run. As you can see from this book, sometimes the red and black ink printed a bit more askew. (You can find a tidier example of two-color printing at this earlier blog post.)

So here's where I really love this: the printers, after making this mistake, recognize it, and want, understandably, to fix it--which means running the entire thing through the press for a third time! Oh, the labor of it all!

That's what I'm going to think of at the start of the fall: sometimes learning and teaching doesn't happen on the first try, or even the second. But that's no reason to stop working! This is also a good reminder of how much of what we do is serendipitous--looking up this book in the catalogue, there was no sign of this cool printing tidbit. It was only because Caitlin looked through every single page in this book with her eyes wide open that she found it. What a nice reward for her curiosity! And that feels like another excellent piece of advice for all of us: don't forget to be curious along the way and to be open to discovering something new.

Happy learning!

(Want to read about printing with red ink in more detail? Joseph Moxon's Mechanick Exercises, as always, is your not-to-be-beat source about early printing; for the section on two-color printing, see pages 328-30. This lovely primer can be found in our catalogue here; a set of zoomable images from it are here.)

Labels:

back to school,

printing,

students,

technologies

Friday, May 15, 2009

tweets not sheets

Looking for pithy thoughts about early modern printing? Wynken de Worde is now on Twitter! You can follow wynkenhimself or just scroll down to the bottom of the right sidebar to see his feed. And it's not procrastination. It's the expansion of his unerring instincts for cross-referencing and promotion that made him the great printer that he was. Um, I mean, is. (Keeping track of the time-period switching and the gender-changing is trickier that you might guess.)

And so that you can more fully appreciate the joke in the title: the sheets in question are of course not sheets on your bed, but the sheets of paper that are the basic unit of measurement for early modern printers, who thought of books--and the cost of books--in terms of the number of sheets it took to print them. Funny, right? That Wynken, he's got a sense of humor.

And so that you can more fully appreciate the joke in the title: the sheets in question are of course not sheets on your bed, but the sheets of paper that are the basic unit of measurement for early modern printers, who thought of books--and the cost of books--in terms of the number of sheets it took to print them. Funny, right? That Wynken, he's got a sense of humor.

Labels:

technologies

Monday, February 16, 2009

democratizing early english books

So after my last post, I've been thinking about what it means to make digital early modern books available in the sort of democratic access that Darnton hopes for in an Digital Republic of Learning. My final point, in that post, was that when my students are first confronted with early English books, they don't know how to make sense of them.

Here's one example of the sort of book that might perplex them:

Just looking at the page opening brings up some of the details that estrange us from early books: the catchwords at the bottom of the page, the signature marks, the fists and marginal comments. None of those are details that we are used to seeing in how today's books are laid out. And then there's the text:

This is a pretty straightforward and easy-to-read example. But even so, there are the long s's that look like f's, the non-standardized spelling, the interchangeable (by modern standards) u's and v's and i's and j's. (This image is from John Brinsley's 1612 Ludus literarius: or, the grammar schoole, an appropriate choice, I thought, for thinking about learning and the connections between learning and reading and writing. Don't forget to note your scripture in the margins! A zoomable image of the page opening is here--although you'll need to have your pop-up blocker turned off--and the catalogue listing is here.)

What about this for being accessible?

That's not as easy to read. It's not simply that it is in a gothic font, although that doesn't help--it's not a font we're used to today. But there are different letter forms even in that font: there are two different forms of "r," for instance, as seen in the last two words in the seventh line. There are also different spellings than we are familiar with, not to mention the different vocabulary. There's also the use of abbreviations, such as the thorn (what we would describe as a "y") with a superscript "t" in the fifth line. And then there's the second line which is too long to fit on one line, and so the final letters spill over onto the third line, marked off with the bracket.

What is this text? It's the start of the Nun's Priest's Tale, from Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, here shown in an edition printed by Wynken de Worde (my man!) in 1498. Here's a transcription (I have not regularized u/v or made any other changes):

Those of you who know this text might notice, too, that it doesn't match up exactly with today's standard texts, and I'm not talking about how the spelling changes from one text to the next. At some point in the transmission from the surviving manuscripts of Canterbury Tales to this printed text, some of the words have changed (is the cottage narrow or poor?). Such are the joys of working with early texts. And I mean that seriously--I love that texts change as we transmit them.

So does putting early English books online make them accessible? My Chaucer example might be a bit loaded--part of what makes that book hard to read is Chaucer's language, which is distant from ours in ways that are assisted by glosses or teachers (although I do think that it's possible to understand the Tales without such aids, if you read patiently). But that is what early printed Chaucer looks like. And my first example doesn't have that problem--there are no big vocabulary obstacles and no strange printed letter forms to confuse us. But it still holds itself apart from us through the way that it appears.

I am certainly not suggesting that early modern books should not be made accessible through digital surrogates. (And there's a whole other post to be done on what digitization cannot do for us.) But it is helpful, I think, to remember that early modern books are not necessarily ever accessible without an apparatus that has been generated either in the classroom or through other forms of scholarly attention and intervention.

I don't think that Darnton doesn't know this. He certainly does. But in the discussion of what digitization means, I find it helpful to remember that access does not mean understanding. And looking back at early printed books can help us remember the ways in which texts and learning and reading are not always easily aligned.

And now to close with something pretty! Here's the lovely woodcut illustration and the marginal annotation summarizing the tale that starts things off (zoomable image of the page opening here; catalogue entry here).

Here's one example of the sort of book that might perplex them:

Just looking at the page opening brings up some of the details that estrange us from early books: the catchwords at the bottom of the page, the signature marks, the fists and marginal comments. None of those are details that we are used to seeing in how today's books are laid out. And then there's the text:

This is a pretty straightforward and easy-to-read example. But even so, there are the long s's that look like f's, the non-standardized spelling, the interchangeable (by modern standards) u's and v's and i's and j's. (This image is from John Brinsley's 1612 Ludus literarius: or, the grammar schoole, an appropriate choice, I thought, for thinking about learning and the connections between learning and reading and writing. Don't forget to note your scripture in the margins! A zoomable image of the page opening is here--although you'll need to have your pop-up blocker turned off--and the catalogue listing is here.)

What about this for being accessible?

That's not as easy to read. It's not simply that it is in a gothic font, although that doesn't help--it's not a font we're used to today. But there are different letter forms even in that font: there are two different forms of "r," for instance, as seen in the last two words in the seventh line. There are also different spellings than we are familiar with, not to mention the different vocabulary. There's also the use of abbreviations, such as the thorn (what we would describe as a "y") with a superscript "t" in the fifth line. And then there's the second line which is too long to fit on one line, and so the final letters spill over onto the third line, marked off with the bracket.

What is this text? It's the start of the Nun's Priest's Tale, from Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, here shown in an edition printed by Wynken de Worde (my man!) in 1498. Here's a transcription (I have not regularized u/v or made any other changes):

A poore wydow somdele ystept in ageOh, yeah, there's one other difficulty in reading this: no punctuation!

Was somtyme dwellyng in a pore cotage

Besyde a groue stondyng in a dale

This wydow of whyche I telle you my tale

Syn that day that she was last a wyf

In pacyence ledde a full symple lyf

For lytyll was her catell & her rent

By husbondry of suche as god her sent

She fonde herself & eke her doughters two

Thre large sowys had she and nomo

Thre kyne & eke a shepe that hyght malle

Well soty was her bour & eke her halle

In whyche she ete many a slender meel

Of poynaunt sauce ne knewe she neuer a deel

Those of you who know this text might notice, too, that it doesn't match up exactly with today's standard texts, and I'm not talking about how the spelling changes from one text to the next. At some point in the transmission from the surviving manuscripts of Canterbury Tales to this printed text, some of the words have changed (is the cottage narrow or poor?). Such are the joys of working with early texts. And I mean that seriously--I love that texts change as we transmit them.

So does putting early English books online make them accessible? My Chaucer example might be a bit loaded--part of what makes that book hard to read is Chaucer's language, which is distant from ours in ways that are assisted by glosses or teachers (although I do think that it's possible to understand the Tales without such aids, if you read patiently). But that is what early printed Chaucer looks like. And my first example doesn't have that problem--there are no big vocabulary obstacles and no strange printed letter forms to confuse us. But it still holds itself apart from us through the way that it appears.

I am certainly not suggesting that early modern books should not be made accessible through digital surrogates. (And there's a whole other post to be done on what digitization cannot do for us.) But it is helpful, I think, to remember that early modern books are not necessarily ever accessible without an apparatus that has been generated either in the classroom or through other forms of scholarly attention and intervention.

I don't think that Darnton doesn't know this. He certainly does. But in the discussion of what digitization means, I find it helpful to remember that access does not mean understanding. And looking back at early printed books can help us remember the ways in which texts and learning and reading are not always easily aligned.

And now to close with something pretty! Here's the lovely woodcut illustration and the marginal annotation summarizing the tale that starts things off (zoomable image of the page opening here; catalogue entry here).

Labels:

Chaucer,

digitization,

technologies

Wednesday, December 10, 2008

Folger digital image collections, part 1

So, speaking of techonology, the Library has recently opened up a very cool new tool: you can now search the Folger's digital image collection from the luxury of your own computer! It's fun for playing and fun for research--although, really, is there a difference?

Our whole collection isn't digitized, of course. But there are some real gems in there. All the images that I use in this blog, for instance, are in the digital collection. Things end up in our digital collection via a couple of different routes. Sometimes a researcher requests specific images for use in a project: our photography department, headed by Julie Ainsworth, takes photos, and those get placed in the collection. Sometimes Library staff requests images for our publications, including our website and online exhibitions. Works also get digitized for use in the classroom, for instance for use in the undergraduate seminars and the Folger Institute's paleography classes.

There are also some larger initiatives to digitize parts of the collection. Most recently, and spectacularly, the Library digitized all pre-1640 Shakespeare quartos in our collection (with the exception of the few that weren't in condition to be photographed). I should repeat that: all pre-1640 quartos. Not one copy of each imprint, but all. How excellent is that? Really, extraordinarily excellent. And I'm not just saying that.

To find out more about accessing the digital image collection, either via the Folger's website or by installing Luna Insight software, see our information page. Once you're in the collection, you can browse, you can search for specific authors or works, or you can search by keywords. It can take a bit of playing to find things (the keyword searches are matched to the catalogue entries, and not necessarily to what is in the image). But I love what I find, even when I'm looking for something else. And when you do find something you want to work with, you can even download it!

(You'll see that you have the option of accessing Insight via your browser or by installing client software. It's definitely worthwhile installing the software--there is lots of stuff that you can do with the software that you can't from the browser, like accessing only the Shakespeare Quarto project. There are more options for downloading, too, like exporting a raw html page. More on those toys next time.)

So what's the image above? It's something I found while browsing the collection and it seemed apropros for this post. It's a detail from a 1700 edition of Johann Comenius's Orbis sensualium pictus, a book best described by the continuation of its title in English: Comenius's Visible world. Or, a picture and nomenclature of all the chief things that are in the world; and of mens employments therein . . . for the use of young Latine scholars. This particular picture is a detail showing a scholar at work in his study. What are the numbers in the picture? They're keyed to the English and Latin vocabulary words that are illustrated! I'll show more from this book in a future post. But for now, you can find information about the book in our online catalogue. And you can find the picture itself by doing a data field search for it in Luna Insight with the image root file number 7988; you can see the full page in image root file 1386.

The beauty of the digital image collection and the public's access to it are the results of the hard work of some key Folger staff: Julie Ainsworth, Head of Photography; and Jim Kuhn, Head of Collection Information Services. Kudos and thanks to both of them, and the many others, who made this happen.

And to all of you, happy playing!

Labels:

Comenius,

libraries,

research tools,

technologies,

woodcuts

Monday, December 1, 2008

more on book technologies, or, "the book is like a hammer"

Just after my last post, a few more items related to books and technologies came across my radar. (Okay, most of those items were in the Sunday New York Times, but I do spend a lot of my Sundays reading the newspaper.) Some quick mention of them here, then.

First up was an opinion piece by James Gleick about digital books and traditional publishing. There's been a lot of gloom and doom about the end of the book. Most of it is ridiculous: books are not dying, they are not about to disappear. But there are some things that are definitely shifting: book sales are down (though I'd say that has less to do with competition from digital texts and more from poor publishing and bookselling practices, in which there has become less and less room for individual taste and outliers) and textbook costs are ridiculously high. What I like about Gleick's piece is his recognition that books are two things: physical objects and texts.

As a physical object, the technology of books is brilliant. The Built-in Orderly Organized Knowledge Device joke from an earlier post gets at exactly how amazingly books do their job. As Gleick puts it,

I'm not going to go into the agreement that Google has struck with the Authors Guild, which is where Gleick goes. But Gleick makes some good points that just as the technologies for delivering text and information change, it does not necessarily mean that the technology that is the book disappears. Indeed, perhaps it means that the purpose of that technology--to deliver text--can take on a new life and reach a new audience. Books want to be read. I have a hard time being against new ways of making more texts reach more people.

So if Gleick focuses on the technological purpose of books as text and information delivery systems, elsewhere in the Times, the Style writers suggest the value of books as objects to be objectified. In their gift-giving guide (perfect gifts for less than $250!!), books crop up twice as great holiday presents.

First is the recommendation that "Old best sellers are affordable first editions. Assorted titles from $50." It's helpfully illustrated with a photo of Rabbit is Rich, What We Talk about When We Talk about Love, and Mona Lisa Overdrive (no information is provided on whether we should infer we should stick with dead, or nearly dead, white men, or if other best-selling authors will do).

Second, and much more weird, are "Classics that are a snap to read. Book covers painted on wood, $150, by Leanne Sharpton" with pictures of The Call of the Wild, The Master and Margarita, Tess of the d'Ubervilles, and Oliver Twist. I'm not sure what to make of them, or of the juxtaposition between the $50 first editions and the $150 wood blocks. Read one, I guess, and display the other. Although I suspect the editors have in mind displaying both.

Personally, if I'm going to be buying a book as an object, I'm going to go with a purse. Caitlin at Rebound Designs turns old, unwanted books into purses. It's the ultimate pocketbook! I have one that features square dancers, but there are a wide variety from which to choose, and she'll even do custom orders. Plus, if you want, she'll give you the guts of the book along with the purse made from its covers. Now that's technology!

First up was an opinion piece by James Gleick about digital books and traditional publishing. There's been a lot of gloom and doom about the end of the book. Most of it is ridiculous: books are not dying, they are not about to disappear. But there are some things that are definitely shifting: book sales are down (though I'd say that has less to do with competition from digital texts and more from poor publishing and bookselling practices, in which there has become less and less room for individual taste and outliers) and textbook costs are ridiculously high. What I like about Gleick's piece is his recognition that books are two things: physical objects and texts.

As a physical object, the technology of books is brilliant. The Built-in Orderly Organized Knowledge Device joke from an earlier post gets at exactly how amazingly books do their job. As Gleick puts it,

As a technology, the book is like a hammer. That is to say, it is perfect: a tool ideally suited to its task. Hammers can be tweaked and varied but will never go obsolete. Even when builders pound nails by the thousand with pneumatic nail guns, every household needs a hammer.He's not interested in fetishizing the book as an object, but in recognizing its utilitarian value:

Now, at this point one expects to hear a certain type of sentimental plea for the old-fashioned book — how you like the feel of the thing resting in your hand, the smell of the pages, the faint cracking of the spine when you open a new book — and one may envision an aesthete who bakes his own bread and also professes to prefer the sound of vinyl. That’s not my argument. I do love the heft of a book in my hand, but I spend most of my waking hours looking at — which mainly means reading from — a computer screen. I’m just saying that the book is technology that works.But Gleick also points out that there are some texts that are better delivered through a different technology. Encyclopedias are at the top of his list, and phone books. The Oxford English Dictionary is perhaps the best example of a book that delivers its text now extraordinarily well digitally--the OED would not be as flexible and wide-ranging of a tool as it now is if it only existed in its multi-volume, occasionally published paper form.